Embeddings let software work with meaning rather than just matching words, so you can search by intent, find related content, and give LLMs the right context to answer questions. In this post we will start from first principles, show what these vectors actually are, explain their useful properties, and then generate and search them locally in Python using small open models, with a worked cosine similarity example you can turn into a graphic.

What Are Text Embeddings?

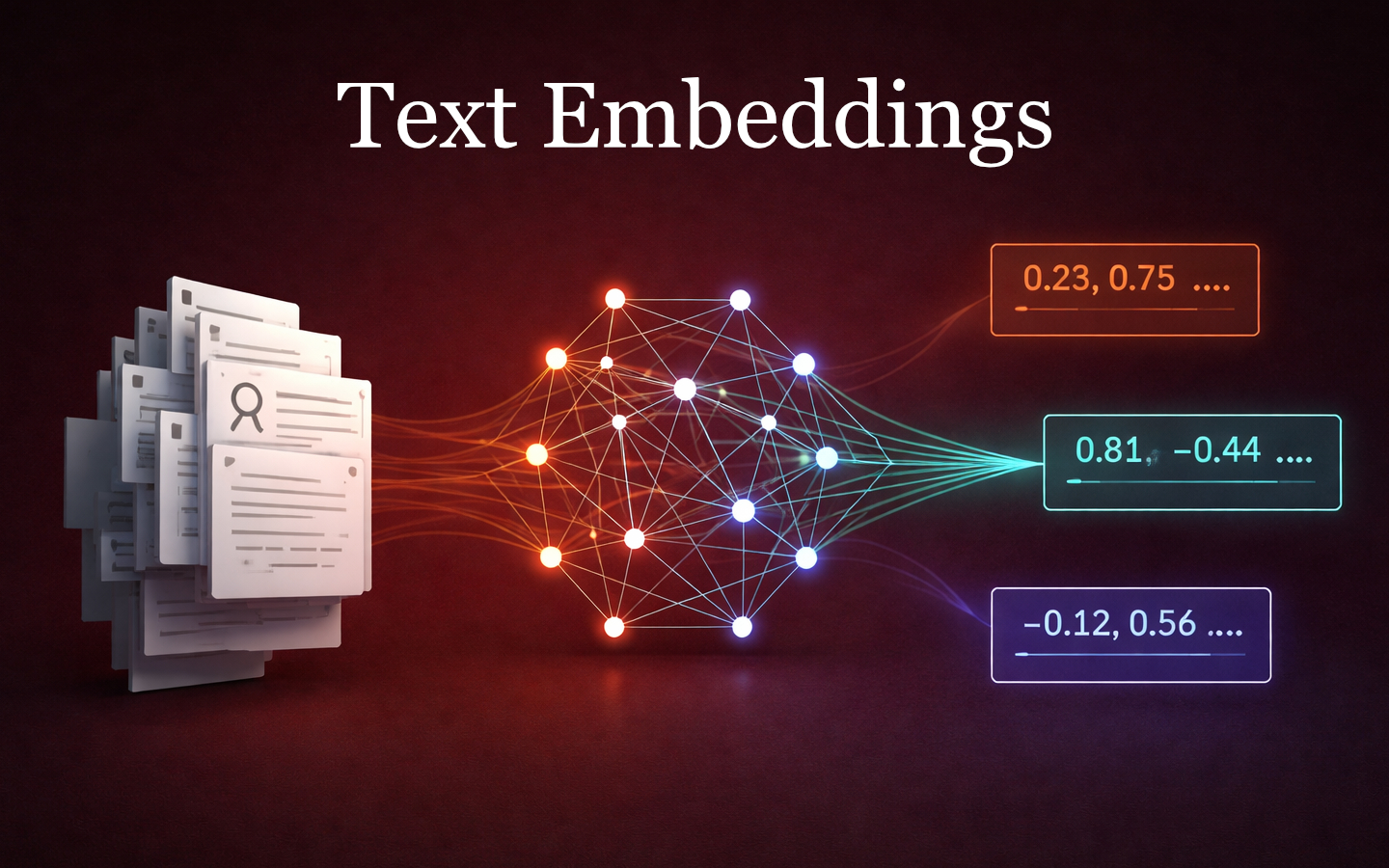

A text embedding is a piece of text projected into a high-dimensional latent space and represented as a vector of numbers. Texts with similar meaning end up close together in this space, which unlocks similarity search, clustering, and retrieval. Transformers make this possible by processing whole sequences with attention and adding a positional encoding vector to each token embedding so that order still matters. The encoder returns a vector per token and we pool those into a single sentence or document embedding for tasks like search and retrieval. Models like GPT use this Transformer attention system when processing user requests, and the T in GPT refers to the Transformer architecture.

What features do these vectors have?

- Dimensionality: models map text to a fixed-size vector such as 384 dimensions for

sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2. - Similarity: cosine similarity between two vectors is a strong proxy for semantic similarity.

- Structure: related texts form clusters in the space, which you can visualise to spot themes and topics.

- Trainability: many models are trained with a contrastive objective on large sentence-pair datasets so semantically similar pairs are pulled together.

How Vectors Turn Into Better Answers

Once you have an embedding for each item in your data, you can embed a user’s query and compare it to everything you have. The closest vectors are the most semantically related items, which means you can search by meaning rather than matching keywords. This same pattern powers semantic search, recommendations, and retrieval-augmented generation by quickly finding relevant passages to feed into an LLM. Specialised vector stores and engines such as FAISS use Approximate Nearest Neighbour techniques like HNSW and IVF-PQ to make similarity search fast at scale.

A Few Embedding Models To Explore

sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2: a compact and efficient model that maps sentences and paragraphs to 384-dimensional vectors for tasks like semantic search and clustering.sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2: a larger model prioritising higher accuracy, often ranking well on semantic similarity and retrieval tasks.sentence-transformers/paraphrase-multilingual-MiniLM-L12-v2: a multilingual model that produces comparable vectors across 50+ languages so similar meaning aligns even when the language differs.

Hands-On: Generate Embeddings Locally In Python

The two examples below use the Sentence Transformers library to create embeddings on your machine and compare them with cosine similarity.

Encode sentences and measure similarity

This compares an English-only style model with a multilingual one and shows how cross-language pairs behave.

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

from sentence_transformers.util import cos_sim

models = [

"sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L12-v2",

"sentence-transformers/paraphrase-multilingual-MiniLM-L12-v2",

]

sentences = [

"The weather is lovely today.",

"Hace un tiempo magnífico hoy.",

"He drove to the stadium.",

"Fue en coche al estadio.",

]

for model_name in models:

print(f"\nResults for {model_name}")

model = SentenceTransformer(model_name)

embeddings = model.encode(sentences)

print("Similarity: weather EN vs ES ->", cos_sim(embeddings[0], embeddings[1]).item())

print("Similarity: stadium EN vs ES ->", cos_sim(embeddings[2], embeddings[3]).item())

print("Similarity: weather EN vs stadium EN ->", cos_sim(embeddings[0], embeddings[2]).item())

You should see the multilingual model assign higher similarity to the English–Spanish pairs and lower scores to unrelated pairs, while the English-only model will not align the cross-language pairs.

Build a tiny semantic search

This embeds a small corpus and a natural-language query, then ranks results by cosine similarity.

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

from sentence_transformers.util import cos_sim

corpus = [

"Yams are perennial herbaceous vines cultivated for their starchy tubers.",

"The stadium was full as the team walked onto the pitch.",

"It is sunny and warm today with clear skies.",

"Tubers are enlarged structures used as storage organs in some plants.",

]

query = "Where is the food stored in a yam plant?"

model = SentenceTransformer("sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2")

corpus_emb = model.encode(corpus)

query_emb = model.encode([query])[0]

scores = cos_sim(query_emb, corpus_emb)[0]

top_k = 3

top_results = sorted(enumerate(scores), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)[:top_k]

print("\nTop matches:")

for rank, (idx, score) in enumerate(top_results, start=1):

print(f"{rank}. {corpus[idx]} (score={score.item():.4f})")

You should see plant biology sentences rise to the top because the query and those passages land close together in the embedding space.

How Cosine Similarity Compares Vectors

If we think of vectors as high-dimensional arrows, each one starts at a common origin and points in a particular direction. The arrow’s length (its magnitude) mostly reflects how big or wordy a message is, while the direction carries the meaning captured by the embeddings model. Cosine similarity deliberately downplays length and focuses almost entirely on direction. Two arrows of very different lengths can still be considered highly similar if they point the same way, because they’re expressing the same idea.

Cosine similarity compares two vectors and produces a score between –1 and 1:

1means they both point in exactly the same direction.0means they are at right angles and represent unrelated concepts.-1means they point in opposite directions, representing conflicting ideas.

A useful mental model is people walking. Two people heading the same way are aligned, one walking north while another walks east has little in common, and one walking north while the other walks south is directly opposed. That’s why cosine similarity works so well for text and embeddings: it compares meaningful direction, not raw size.

Practical Tips

- Start simple: a compact model like

all-MiniLMis fast and good enough for many prototypes. - Go multilingual only if you need it: multilingual models align meaning across languages but are larger and may be slower.

- Use cosine similarity consistently: embed your data and your queries with the same model and compare with cosine similarity.

- Track model versions: if you change models your vectors change too, so keep a note and re-embed when you upgrade.

Wrapping Up

Embeddings map text into a vector space where meaning is measurable, which lets you retrieve relevant content by intent rather than keywords. You have seen what these vectors are, why they are useful, and how to generate and search them locally with a couple of small models. Try the examples with your own sentences, swap in the multilingual model when needed, and experiment with different queries to see how the space behaves. In an upcoming post we will add data to a vector database for a RAG system over a document and we will use an OpenAI embeddings model for that.