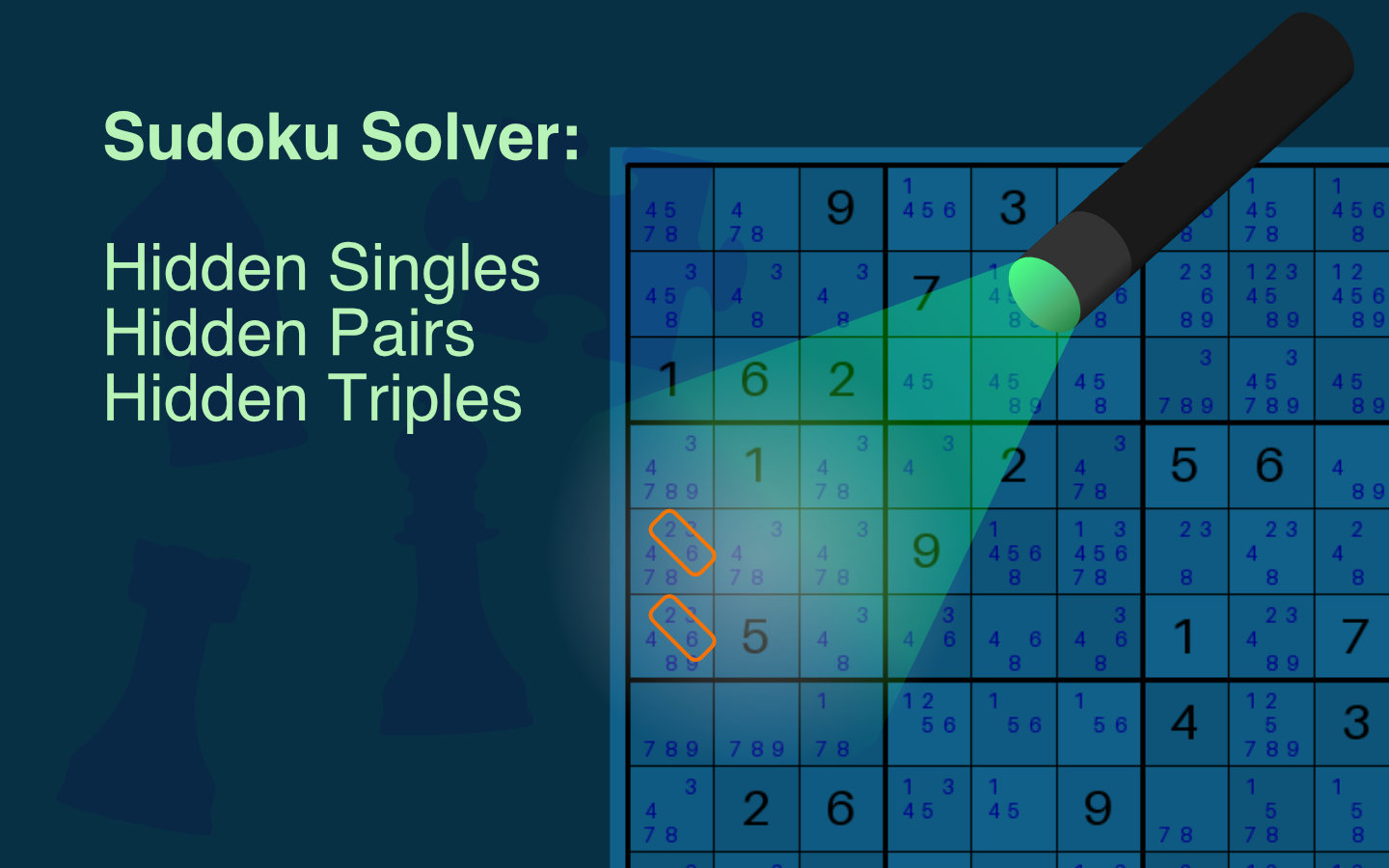

In the last Sudoku Series blog post we implemented the naked pair and the naked triple rules. In this post, we will look at implementing the hidden single, hidden pair and hidden triple rules. Applying these rules is documented on many websites, but the two I’ve liked during my research are Mastering Sudoku and Sudoku.com.

If you like this post and you’d like to know more about how to plan and write Python software, check out the Python tag. You can also find other posts in the Sudoku Series.

What are the Hidden Set Rules?

The hidden set rules use logical deduction to identify groups of cells with unique candidate numbers that are hidden among other candidates:

- The cells are located within the same block, row, or column.

- The number of unique candidates hidden within those cells is equal to the number of cells identified.

These form a hidden set, meaning the candidates in the set only appear in those specific cells within the region, even if other candidates are present. As a result, other candidates in those cells can be eliminated, narrowing down possibilities and aiding puzzle solving. This concept is often easier to understand through images and concrete examples demonstrating what to look for.

Hidden Singles

A hidden single is the simplest form of the hidden set rules. This occurs when exactly one candidate number appears in only one cell within a block, row, or column, even if that cell contains multiple candidates.

Because that candidate number cannot appear anywhere else in the region, it must be placed in that particular cell. This allows us to eliminate all other candidates from that cell, effectively solving it.

Consider the state of a row of the board where a hidden single is present, but not immediately obvious, among other candidates.

In this example, the candidate 4, highlighted in green, appears only once in the row, hidden among other candidates in the cell.

Although the cell contains multiple candidates, since 4 cannot be found anywhere else in the row, it must go in that cell.

Removing the 9 candidate from this cell simplifies the puzzle and assists in solving subsequent steps.

Hidden Pairs

A hidden pair occurs when exactly two candidate numbers appear only in the same two cells within a block, row, or column, even though those cells may contain additional candidates.

Because these two candidates cannot appear anywhere else in the region, they must be placed in those two cells. This allows us to eliminate all other candidates from those cells, simplifying the puzzle.

Consider the situation above where a row has candidates 3 and 7 , marked in green, that appear in exactly two cells, but those cells also contain other candidates.

By identifying this hidden pair, we can confidently remove all other candidates, marked red, from these two cells.

Hidden Triples

A hidden triple is the next step up from the concepts above. It occurs when exactly three candidate numbers appear only in the same three cells within a block, row, or column, even if those cells contain other candidates.

Just like with hidden pairs, because these three candidates cannot appear anywhere else in the region, they must be placed within those three cells. This allows us to eliminate all other candidates from those cells, simplifying the puzzle further.

To identify a hidden triple, look for three candidates that occur exclusively in three cells, even if those cells contain additional candidates. Remove all other candidates from the cells.

Cells Missing Candidates from the Set

When working with hidden sets, it is important to understand that not all cells in a pair or triple need to contain every candidate from the set. Cells can still be part of a hidden pair or triple even if some candidates are missing from individual cells, as long as the candidates collectively appear only within those cells.

For example, in a hidden triple involving candidates 3, 5, and 8, the three cells might contain candidates as follows: 3 and 5 in the first cell, 5 and 8 in the second, and 3 and 8 in the third.

As long as no other cells in the region contain candidates 3, 5, or 8, this situation still forms a hidden triple.

We know that these candidates must exist among those three cells, allowing us to remove all other candidates from those cells.

Implementing These Rules

The current code at the time of writing can be found on GitHub where you can also see the pull request for the changes in this post.

Hidden Sets Implementation

I knew that the hidden singles, pairs, and triples would require fairly similar implementations, so I decided to extract a common method that can find hidden sets in any quantity in the region. This allows us to implement each of the hidden set rules in a single line each.

def apply_hidden_single_rule(grid: Grid) -> bool:

return _apply_hidden_set_rule(grid, size=1)

def apply_hidden_pairs_rule(grid: Grid) -> bool:

return _apply_hidden_set_rule(grid, size=2)

def apply_hidden_triples_rule(grid: Grid) -> bool:

return _apply_hidden_set_rule(grid, size=3)

The method these are calling does a number of things to find and apply the hidden set rule.

Finding Sets in each Region

for region in grid.region_iter():

# Create list of candidates in the region

counts = Counter(candidate for cell in region for candidate in cell.candidates)

valid_candidates = {

candidate for candidate, count in counts.items() if count <= size

}

The first thing we do while iterating over all 27 regions of the grid is to count up how many copies of each candidate there are in the region.

Counter is imported from the collections module and it allows us to iterate over all the items in an iterator and count up the number of instances.

We then reject any candidates that appear more times than the size of the set we’re looking for, since they cannot be part of a hidden set if they exist more times than the size of the set in the region.

Next, we create possible combinations of candidates that might form a hidden set.

If you’ve followed the last post on this topic, you’ll know that the combinations function finds all the ways to combine the items of an iterable into groups of a given size.

Once we form these combinations, we need to check each one to see if it is a valid hidden set.

# Work through all possible combinations of valid candidates

for combination in combinations(valid_candidates, size):

# Convert the tuple to a set

set_candidates = set(combination)

# Get a list of all the cells with any candidate

affected_cells = [

cell for cell in region if set_candidates.intersection(cell.candidates)

]

# Move on if the number of affected cells doesn't match the set size

if len(affected_cells) != size:

continue

# Found a valid hidden set!

complementary_candidates = ALL_CANDIDATES - set_candidates

for cell in affected_cells:

if len(cell.candidates) > size:

applied = True

cell.candidates -= complementary_candidates

First we convert the combination into a set so we can use set operations on it.

By taking the intersection of it against each of the cells in the region, we can get all the cells that contain any one of the candidates from the combination.

At this point, if the number of affected cells doesn’t match the size of hidden set we’re looking for, we don’t have a hidden set and we can continue to the next combination.

Otherwise, we now know we have a hidden set and we need to remove the other candidates from the cells.

We create a set of candidates that are everything except the candidates in our hidden set.

For each affected cell, we check that the cell has more candidates than the size of the set before changing applied to True.

We remove the cell candidates that are not part of the set, and we’re done.

Applying All Our Rules

We can add our new rules to those already being applied to the Solver, given us the following.

applied = (

apply_single_candidate_rule(self.grid)

or apply_naked_pairs_rule(self.grid)

or apply_naked_triples_rule(self.grid)

or apply_hidden_single_rule(self.grid)

or apply_hidden_pairs_rule(self.grid)

or apply_hidden_triples_rule(self.grid)

)

applied will only become True if at least one solver makes a change to the grid.

When that happens, either the grid is solved or we haven’t yet implemented complex enough rules to solve the puzzle.

This is a pattern which is proving to work for the Sudoku Solver so we will continue this way until something no longer works.

Testing Our Code

Like for the naked sets, we have added new tests for these new rules. It starts to become hard to create full grids for these rules that provide exactly what you want to perform a good test. So I opted, this time, to start with a grid that has all candidates available on all cells, and just manually modify the candidates to fit the pattern we’re looking for.

This appears to have worked well and so I will probably use this technique going forward as well.

Wrapping up

You’ll probably notice that I haven’t shown any examples of actually solving puzzles we couldn’t solve before. That’s because, disappointingly, this rule hasn’t helped solve our expert puzzles yet. We’ll implement more complex rules soon, and then they will be solvable.

I have a feeling I’ve missed a minor edge case here, and will update the tests accordingly between this post and the next to fix it.

I think if there are three cells with, for example, candidates (3, 5, 9), (3, 7, 9) and (5, 7, 9) where they form a hidden triple for (3, 5, 7), I don’t think applied will be changed to True.

This could lead to situations where applying this rule actually did change the grid, but the solver stops, so this should get fixed.